#12 Bausch & Lomb Portrait Unar 380mm f4.5

I’ve got a unique optical layout and a silhouette so distinctive you can spot me from a distance. My construction is absurdly complex and notoriously temperamental. I’m a portrait virtuoso, lurking modestly in the shadows but towering over many of my peers like a smug diva. I am Unar. Portrait Unar.

So one day over at Bausch & Lomb, they sat down and decided it was about time to give TTH's portrait triplets a good kick in the nuts. Those lenses had been successfully annoying the competition since 1898.

Behind the cryptic acronym TTH hides none other than the illustrious English firm Taylor, Taylor & Hobson. Their immortal fame came mainly from the Cooke portrait series, famous for offering adjustable soft focus. Every Tom, Dick and Harriet knew their Series II (f3.5–f4.5) and VI (f5.6), with the trademark soft-focus control that looked like brass knuckle dusters. Hence the informal and well-established nickname: Knuckler. These were among the first anastigmats with variable diffusion, and for the next fifty years they became an integral part of portrait photography. They also caused every damn lens maker on the planet to desperately want their own Knuckler.

B&L weren't about to miss that party. Together with their German BFF Zeiss, they rolled up their sleeves and in 1904 hammered out the Unar. But hold your horses. The story is more twisted than that.

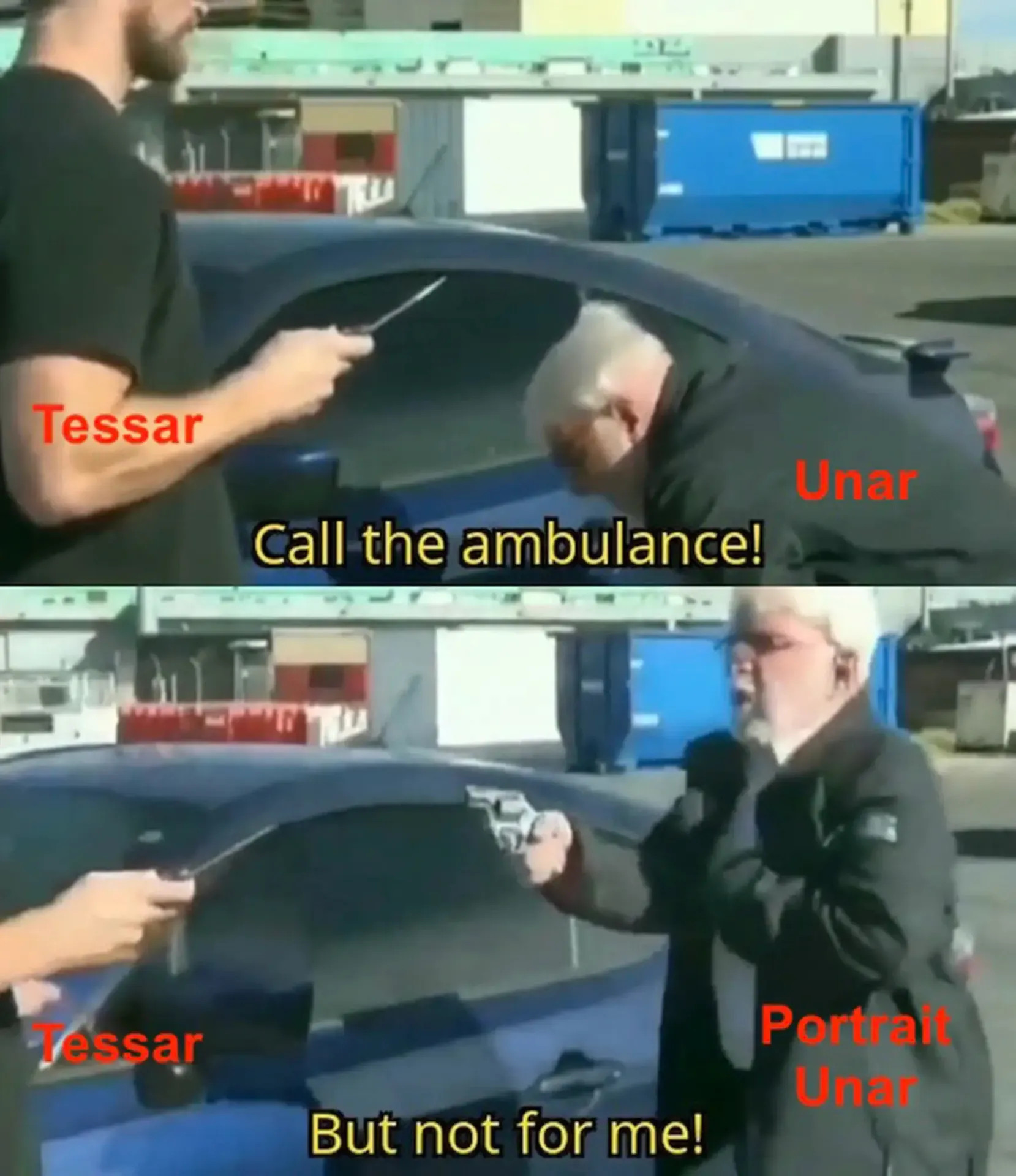

The Unar design was originally calculated at Zeiss by Dr. Rudolph in 1899. It was a four-element anastigmat with no cemented groups, basically one lens more than your neighbor's Triplet. Unfortunately, the concept aged about as gracefully as mayonnaise in the sun and quickly fell behind the demands of its time. The original Unar (before it got the Portrait label and soft-focus option) convulsed in its death throes for a bit, until Zeiss buried it in 1902 with the brand-new Tessar. More precisely, Dr. Rudolph striked again.

Tessar (from Greek τέσσερα, téssera = four) also has four elements, but the last two are cemented into a doublet. You don't need a PhD to see the family resemblance: one evolved from the other. Tessar simply turned out to be the more gifted child and Zeiss loved it more. Unar lost. Tessar became one of the cornerstones of photographic optics.

And by the way, all those companies are still alive and kicking. Bausch & Lomb now makes contact lenses (still lenses! Just for eyes). Taylor Hobson makes metrology instruments, Cooke Optics spun off and builds high-end lenses (their shared history is a soap opera for another time - they're still flirting with soft-focus, see the Cooke PS645), and Zeiss is still busy sticking its fingers into everything.

So what about 1904? Well, picture this: just like Gandalf the Grey fought the Tessar in the mines of Moria, Unar the Brass was out there on the optical ̶P̶e̶l̶l̶e̶n̶o̶r̶ Fields battling Balrog. Or something like that. Point is, both Unar and Gandalf fell, only to come back stronger than ever - Gandalf the White and Portrait Unar.

Behind Unar's phoenix-like resurrection was Zeiss, being just a little bit cheeky. First came Unar. They tweaked it a bit, bam, Tessar was born. But hey, why not squeeze a few more marketing drops out of the soft-focus craze? So they dusted off the Unar design, slapped on a diffuser, gave it a bit of a makeover and voilà - Portrait Unar was born. It wasn't some groundbreaking new design; it was basically the old one with its flaws repackaged as "features." Classic marketing, already working overtime back then.

Now for the truly weird part: the construction. This thing has an aperture mechanism with blades, a rack-and-pinion focusing system and a separate soft-focus slider. The main barrel is made of several nested inner tubes like some optical Matryoshka doll, all connected together. Connected precisely together by tiny screws roughly the size of the close buttons on internet ads. Move one of those tubes by a yoktometer and the whole thing is fucked. And as if reassembling it weren't masochistic enough, you've also got to calibrate it perfectly so the aperture scale doesn't start halfway through. Trial/error. GLHF.

You can't really access most of it properly, and unless you know exactly what you're doing, you might as well get comfy because it's going to be a long night. The number of possible assembly combinations is similar to Rubik's Cube and only one of them actually works. I found that out the hard way. After hours of intense cursing I managed to put it back together and even had a screw left over. I decided it was a factory-installed self-destruct feature.

The moving tubes inside the barrel come with a little surprise: friction. Unars are notoriously stiff when you move the rack-and-pinion or the other sliders. A lot of people assume it just needs "a bit of grease," so they start slathering it like they're basting a Christmas turkey. But the culprit is simply friction. Lots of tubes + lots of surface area = lots of friction. All you can really do is clean it and accept that it'll never glide like a Jamaican bobsled team.

Actually, there are two nasty surprises. The second is the infamously disgraced aperture. The blades were made from cellulose, which was brittle and not exactly known for its longevity. It didn't take long for them to simply rot away. Finito. And the ones that didn't crumble on their own usually met their doom at the hands of some enthusiastic DIY person, who under the noble pretense of cleaning (see above) dissolved them with wide-eyed horror. That's why the vast majority of Unars have no diaphragm blades left, and all you can do is spin the aperture ring and pretend. But honestly, who was going to stop the lens down anyway? They were basically just forcing you to shoot wide open and bathe in all that bokeh and character. Aha!

- To be fair, Bausch & Lomb were experts at this not just with the Unar. Their Petzvals and other models from the same period suffered from similar issues, though less dramatically. If you ever find one with an intact aperture, there are only two explanations: you just won the lottery and you'd better not even look at that diaphragm the wrong way, or It's a modern restoration. Which was expensive. Extra expensive². So don't mess with it either.

To give credit where it's due, everything else about the lens is top-notch. This was B&L's showpiece, meant to go head-to-head with TTH, and it shows. The build quality is superb and both the aperture and soft-focus selectors move with a crisp little whoosh that's weirdly satisfying - like the signature "puff" of air you get on a Knuckler when you twist it. The aperture ring sits closer to the flange, while the diffuser scale, marked 1–4, is placed before the diaphragm. One is the sharpest setting, four is the dreamiest mess.

And here's a fun detail for the 0.0042‰ of humanity who might care: the lens screws right onto a Hermagis Eidoscope No.1 flange. So if you're missing a flange and, by some cosmic coincidence, you've got a No.1 Eido lying around, congratulations! Jackpot!

The most striking foreign feature, though, is the set of control rods. Both selectors have unmistakable sliders with holes on each side. They were meant for attaching strings, so the photographer could adjust settings from behind the camera without stepping away from the ground glass. Genius in theory, but considering the aforementioned friction, you'd need Arnold Schwarzenegger to actually pull it off. Still, it looks amazing on the diagrams.

The only other lenses with the same slider system were the Portrait Series A f4, B&L's Petzvals, and the high-speed Series B f2.2. As far as I know, that's it. You won't find this oddball setup anywhere else.

The Portrait Unar series came in four sizes: 10", 12", 14¾", and 18", all at f4.5. The biggest one shows up only sporadically in official catalogues. Apart from the version discussed here, there was also a later redesign that ditched the perforated sliders and moved toward the more modern visual language of lenses like the Plastigmat with double-hatched control rings.

In the attached period records, you might notice some odd code names that look like they belong in a spelling alphabet: Xiar, Ximar, Xilet and so on. No, it's not some Romanian incantation, but telegraphic codes, a standard part of the industry back then.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, if a gentleman wanted to order a lens from across the world, he'd send a telegram. And since telegraph companies charged by the letter or word, manufacturers used short, unambiguous codes instead of spelling out "Bausch & Lomb - Zeiss Portrait Unar, Series 1b, 380mm f4.5." Just send Ximat and everyone knew what you meant. Catalogues included these code tables to make the ordering idiot-proof. Some companies (Zeiss, Voigtländer, Ross, etc.) even registered entire proprietary telegraphic dictionaries to keep their orders clear and foolproof. Voigtländer in particular loved this stuff and their catalogues are basically telegraph nerd heaven.

As for the actual image rendering, Portrait Unar behaves pretty much like other anastigmats of its league. At the lowest soft-focus setting and wide open, the lens gives you pleasantly sharp, portrait-friendly images with just the right amount of contrast. Stop down even a homeopathic amount and sharpness skyrockets. Thanks to its flat-field design, it renders groups beautifully too.

Quick recap: flat-field lenses bend perspective less, so the image stays sharp and well-defined across the entire frame. This makes them excellent for group portraits and essential for technical work.

Curved-field lenses, on the other hand, tend to prioritize the center, with sharpness dropping off dramatically toward the edges. Petzvals and old meniscus optics behave like this. It's perfect for characterful portraits or artistic shots where accurate reproduction of reality isn't exactly a priority.

If you want to crank up the soft-focus effect, you'd better have a trained eye. The diffusion is on the subtle, elegant side. Even at the max setting, don't expect some mushy glow. And that's not a flaw. For this class of lens, that kind of restrained, delicate diffusion is exactly what you want - it smooths out skin and softens wrinkles without turning people into blurry marshmallows.

But don't throw your Unar in the bin just yet, my squishy pictorialist enthusiasts. Here's a little underground trick. If you unscrew the rear cell and use it on its own, you get a surprisingly hardcore soft lens with a rendering reminiscent of a Kodak Portrait. Adapting it isn't exactly a walk in the park, since the flange thread sits inconveniently close to the rear group, but with a bit of DIY skill (of which, tragically, I have next to none) you can elevate the Unar to a whole new level. Sure, you'll lose the diaphragm, soft-focus slider and lens hood, but you'll end up with something like an Oscar Zwierzina Plasticca or a Kronar/Kronarette. Basically, you'll start painting.

As you can see, the Unar is a gloriously non-boring piece of glass, blending the familiar with the unexpected, the earthy with the dreamlike. So next time someone hits you with the usual barrage of questions - "Are you shooting portraits? Landscapes? Nudes? Will it be sharp, natural, soft, pictorialist? Stopped down a lot, a little, somewhere in between?" - your answer is simple: YES.