#11 Dallmeyer 3B 290mm f3

It was forged early in 1883 by old masters in faraway Dallmeyer, and in May of that year it was purchased by a mysterious Mr. Alman, certainly a photographic connoisseur of excuisite tastes. Fast forward 142 years later and it's in the hands of another fancy bloke with an equally voracious optical appetite - and idleness certainly does not await him.

In the previous article, I pondered and mused, among other things, about how only a few of my portrait lenses can currently challenge the Hermagis Portrait and the Fast Worker in the ring without immediately throwing in the towel. On paper, the Dallmeyer 3B seemed like an evenly matched opponent - so how did it turn out? Did the Dallmeyer Series B confirm its legendary status and join the ranks of Hermagis and Hugo Meyer? Or were the tales exaggerated and instead of a triad of equals, only two champions continue to jostle on the pedestal? Whoa not so fast! Let's take a scenic detour. Through London and small Czech town called Kostelec nad Černými lesy.

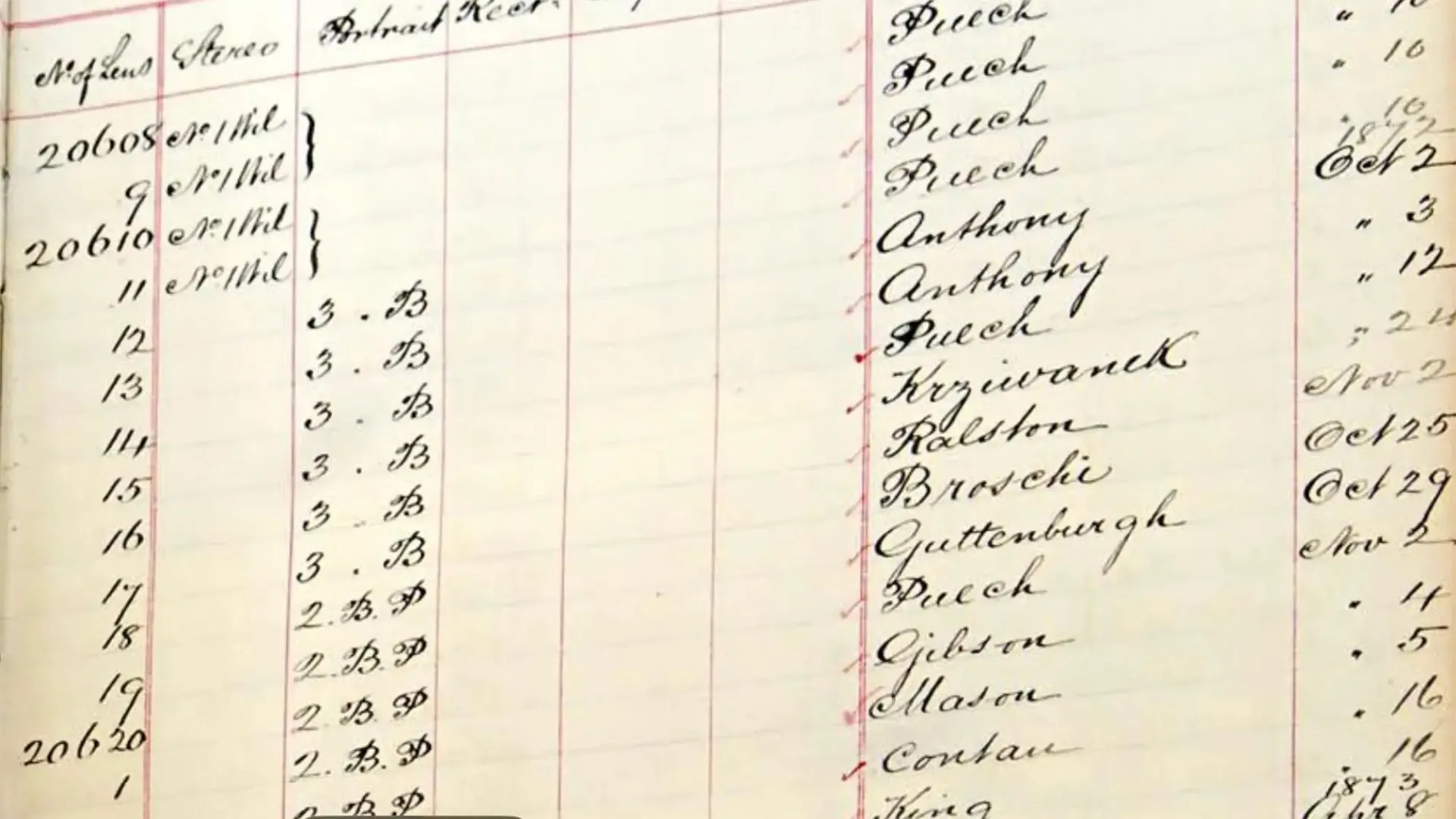

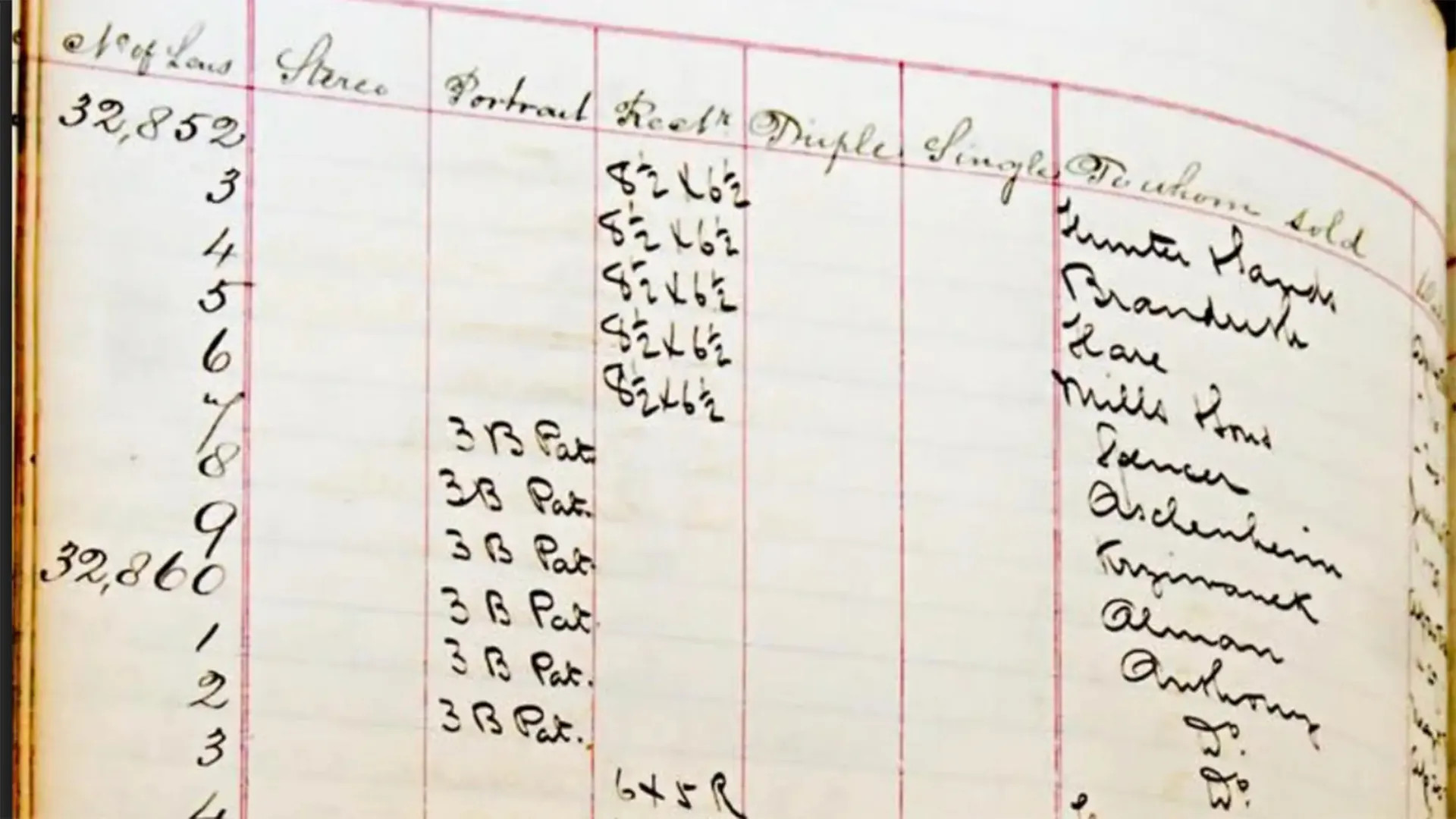

As the lead paragraph already hinted (not that it dropped from the sky - I had to roll up my sleeves and dive headfirst into the dusty annals of the Dallmeyer factory), this lens left the warmth of the assembly bench in May 1883 and was immediately snatched up by a certain Mr. Alman - assuming I'm decoding that damn handwriting correctly. And then? Vanished. Spent the next century and a half who-knows-where, doing who-knows-what.

- If you're willing to poke around their web archive, you can actually dig out a surprising amount of info about the who, what, when, where, and how. Sure, the lists are far from complete and the site sometimes runs like it had a stroke, but let's be grateful it exists at all. That's not always the case. And I don't just mean someone bothered to compile the archives - first they had to bloody survive. Through wars, floods, and generations of people not giving a fuck. And to even have a shot at surviving, someone had to make them in the first place. And no, it doesn't apply to everyone - and yes, I'm looking at you, Swiss Suter.

Now, allow me my blissfully naive fantasy: that for all those decades, this brass beauty was out there relentlessly immortalizing corseted maidens and top-hatted gentlemen. Think of the faces it saw, the stories it witnessed, the places it traveled - if only this golden tube could talk. But let's be honest: it probably spent the last God-knows-how-many years collecting dust in a banana box down in some musty basement, nestled between a dead rat and last decade's Christmas decorations. And then one day, during spring cleaning, someone thought, "Hey, maybe I can flog this." Still - I prefer the corsets and cylinder hats version. Don't ruin it for me.

So where did the B Series come from?

London, of course. Before starting his own business, John Henry Dallmeyer worked under Andrew Ross (and, as a bonus, married off his daughter). Ross was one of the early trailblazers in lens-making, crafting optics as early as 1840. Meaning he was there while the View from the Window at Le Gras was still drying.

And the design of Dallmeyer's B Series is heavily inspired by A. Ross's original portrait line. What you learn from your master, you eventually use to build your own empire. Or, you know, copy with flair.

So, why all the fuss about this lens?

Because it's a bloody masterpiece of craftsmanship. It's optically brilliant, it's got a variable soft-focus mechanism (something Ross didn't bother with) and - most importantly - it's got an aperture of f3. Sure, that doesn't exactly make people going mad nowadays. Every flea market is littered with Chinese crap boasting f0.95 and similar marketing-fueled specs. But here's the catch. No - scratch that. Here's the whopper.

It's the image circle. The coverage. The goddamn photographic battlefield. Most modern lenses barely manage to cover an APS-C sensor without breaking into a sweat. Maybe a full-frame if they're feeling badass (which, for the clueless, is a teeny-tiny 24x36mm, originally derived from one frame of 135mm film. Ha, bet you've always wondered where that weird number actually came from, right?). But this Dallmeyer? This bad boy covers damn near an A4 sheet of paper.

I won't bore you with too many technical details, but here's the kicker: the larger the format, the shallower the depth of field at the same aperture. Shooting at f3 on 135mm film? Meh. You take a portrait, and the whole person's acceptably sharp. Big whoop. But shoot at f3 on something like 8x10"? Oh boy. That's when the magic happens. You nail the eyes, whisper a prayer to Saint Scheimpflug, something twitches by a millimeter and bam - suddenly you're focused on a nostril or the edge of a single damn hair. Depth of field? Razor-thin. Blink and you've missed it.

This kind of thing raises the bar for both the person behind the camera and the poor soul in front of it. The slightest mistake? Enjoy your blurry mess. But when you nail it - really nail it - the depth of field and 3D effect look like they've been beamed in from another dimension. Want to compare it to modern tech? You'd need to build a lens for full-frame that shoots at f/0.4. Let me say that again: f-zero-point-four. And guess what? That's physically not gonna happen. And if by some miracle you did pull it off, it'd be a smudgy puddle of optical diarrhea riddled with every optical failures in our solar system.

- Yeah, yeah, this is the simplified version. For the math fetishists and lens autists out there, feel free to dive into terms like "equivalent aperture," "image circle," "depth of field," or "crop factor."

- But the aperture as fast as that one didn't just serve to please the eye - it also made life easier in the studios of the past. See, back in the day, photographic materials had the sensitivity of a blind mole. Daguerreotypes, Collodion process, you name it - exposures took ages. So faster lenses like this one weren't just sexy, they were revolutionary. They chopped exposure times from dozens of seconds down to fractions of a second. Total game-changer.

There were countless variations, in-between models and Frankenstein hybrids, but let's stick to the two most important iterations. That said, regardless of version, this thing is rare as hen's teeth. Even though quite a few were made, it's still a unicorn. If you've got one - keep an eye on that.

- The earliest versions were from brass, equipped with a rack & pinion focusing mechanism and good old Waterhouse stops (occasionally and very rarely also with iris diaphragm). The soft-focus mechanism was tucked away in the rear and you adjusted it by rotating the rear element. There were notches and an indicator, and the more you unscrewed, the dreamier and more melted the image became. You could go up to about five full rotations. Downside? You had to remove the lens from the camera to adjust it.

- The second version ditched the rack movement and made SF adjustment way less awkward - it moved the control up front. No more brassy juggling. Still golden, still dishy, but now with a standard aperture made of blades controlled by a lever.

Alright, time to bite into that half-eaten apple - how does it actually shoot? Well I hate test shots. Checkered paper, bricks, still life with whatever I found in the room - no thanks. So I decided to skip the foreplay and jump straight into the deep end. Trial by fire. Just take it out into the wild and see what happens. And what better place to do that than the fantastic annual event Umění nás spojuje a.k.a. Art Connects Us in Kostelec nad Černými lesy? (Maybe I'll see you there next time!) There I managed to hunt down a few willing human specimens and put this antique colossus through its paces.

And it shoots… breathtakingly. Granted, I lucked out with unusually disciplined models sporting near-superhuman self-control - no one was twisting, no headrests or chloroform required. Hell, even I didn't budge an inch with my heavy-ass Sinar S 8x10". The results are laying around here (I didn't even stopped down the aperture or increased the softness this time, so these are fully open and razor-sharp to the max), and I'm pretty sure you'll at least agree on one thing: there's a LOT of plasticity, sharpness, and... yeah, I'll say it again - character. So, Hermagis, Hugo Meyer, or Dallmeyer? Well, what's your verdict?